The year 1932 was filled with preparation for the design of the Research House which was to play an important part in the lives of Richard and Dione Neutra and their second son Dion, who became an architect. Neutra considered carefully what he might design, resolved at once to acknowledge the generous patronage of Van der Leeuw, and to demonstrate the latest technology to serve his family’s biological and psychological needs. He named the project the Van der Leeuw Research House to express his intent. Neutra’s progressive design approach was directed to how human organisms behave and survive, especially in restricted space. He wanted to throw new light upon the preconceived cliché of “architecture as a space art” with applied biology, by measuring and observing human responses to various biological and psychological stimuli. The VDL Research House was conceived as a laboratory to demonstrate that restriction of space need not mean a restriction of well-being. He sought every means to give the feeling of space efficiency, of comfortable accommodation in a restricted floor area which he felt would have to be typical for many kinds of housing in future generations.

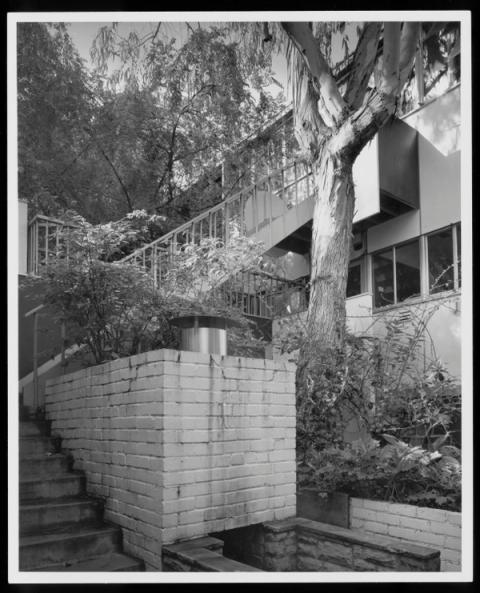

The limited treeless site inspired Neutra to strive to demonstrate his ability to achieve privacy and spacious living despite the constraints and density of the neighborhood. Unlike adjacent one-story low houses, he built vertically to take advantage of the views over the reservoir, the San Gabriel Mountains to the far north, and his own peaceful garden to the rear. For privacy the first floor of the north wall was likewise unbroken. Neutra planted fast-growing trees and other plants to the very edge of the sidewalk, providing solar protection and privacy from Silver Lake Boulevard. Taking advantage of vague enforcement of setback requirements, he built to the street line and to the full 60-foot width north and south as well.

Neutra’s two-story plan with basement and roof deck reflects the dual purpose of the VDL Research House as both home and office. On the ground level was the drafting room suite with its own separate front and rear access. The front entrance door led to a small reception area and Neutra’s personal design studio, connecting by stairway to the family quarters on the second floor. From the sleeping terrace on this floor one could reach by a ship’s ladder the solarium rooftop with its panoramic view across Silver Lake and the opposite shore.

Unlike the experimental metal skeleton of the Health House, Neutra used less costly wood balloon-framing dimensioned to accommodate standard industrial steel window sash, but the modular rhythms and crisp detailing of design gave it some of the same visual qualities. The wood-frame design was also believed to provide elasticity in earthquakes. Prefabricated concrete joists and a suspended slab provided a fire-retardant base for the first floor. Continuous metal casements throughout determined a precise modular system of milled 4 x 4 wood columns. On the front elevation stucco bands emphasized the horizontal lines to the maximum. Panels on the rear elevation were of painted pressed wood. The original house utilized two gravity furnaces with push-button controls. Shading of the second-story windows to the west was provided by a five-foot overhang with an aluminum-faced drop awning at its eave. Below, first-story windows were shielded by a heavy planting of pittosporum and acacias.

The year 1932 was filled with preparation for the design of the Research House which was to play an important part in the lives of Richard and Dione Neutra and their second son Dion, who became an architect. Neutra considered carefully what he might design, resolved at once to acknowledge the generous patronage of Van der Leeuw, and to demonstrate the latest technology to serve his family’s biological and psychological needs. He named the project the Van der Leeuw Research House to express his intent. Neutra’s progressive design approach was directed to how human organisms behave and survive, especially in restricted space. He wanted to throw new light upon the preconceived cliché of “architecture as a space art” with applied biology, by measuring and observing human responses to various biological and psychological stimuli. The VDL Research House was conceived as a laboratory to demonstrate that restriction of space need not mean a restriction of well-being. He sought every means to give the feeling of space efficiency, of comfortable accommodation in a restricted floor area which he felt would have to be typical for many kinds of housing in future generations.

The limited treeless site inspired Neutra to strive to demonstrate his ability to achieve privacy and spacious living despite the constraints and density of the neighborhood. Unlike adjacent one-story low houses, he built vertically to take advantage of the views over the reservoir, the San Gabriel Mountains to the far north, and his own peaceful garden to the rear. For privacy the first floor of the north wall was likewise unbroken. Neutra planted fast-growing trees and other plants to the very edge of the sidewalk, providing solar protection and privacy from Silver Lake Boulevard. Taking advantage of vague enforcement of setback requirements, he built to the street line and to the full 60-foot width north and south as well.

Neutra’s two-story plan with basement and roof deck reflects the dual purpose of the VDL Research House as both home and office. On the ground level was the drafting room suite with its own separate front and rear access. The front entrance door led to a small reception area and Neutra’s personal design studio, connecting by stairway to the family quarters on the second floor. From the sleeping terrace on this floor one could reach by a ship’s ladder the solarium rooftop with its panoramic view across Silver Lake and the opposite shore.

Unlike the experimental metal skeleton of the Health House, Neutra used less costly wood balloon-framing dimensioned to accommodate standard industrial steel window sash, but the modular rhythms and crisp detailing of design gave it some of the same visual qualities. The wood-frame design was also believed to provide elasticity in earthquakes. Prefabricated concrete joists and a suspended slab provided a fire-retardant base for the first floor. Continuous metal casements throughout determined a precise modular system of milled 4 x 4 wood columns. On the front elevation stucco bands emphasized the horizontal lines to the maximum. Panels on the rear elevation were of painted pressed wood. The original house utilized two gravity furnaces with push-button controls. Shading of the second-story windows to the west was provided by a five-foot overhang with an aluminum-faced drop awning at its eave. Below, first-story windows were shielded by a heavy planting of pittosporum and acacias.